You are here

Back to topCharles and Ray Eames: The couple who shapped the way we live

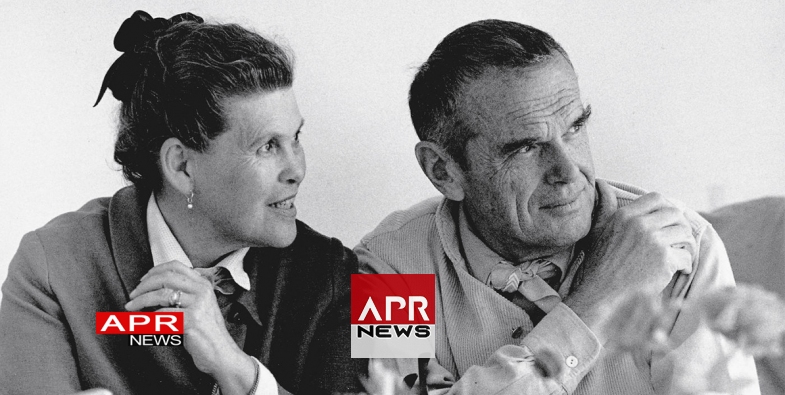

Charles and Ray Eames: The couple who shapped the way we live

BBC - Charles and Ray Eames were two of the most influential designers of the 20th Century. William Cook looks at how the pair worked together to create designs that still inspire today.

Charles and Ray Eames are most famous for their iconic chairs, which transformed our idea of modern furniture, but this was merely one facet of their work. They were graphic and textile designers, architects and film-makers.

If they’d confined their efforts to just one of these genres, we’d still be talking about them today. Yet they spread their talents far and wide, becoming two of the greatest designers of the 20th Century.

In 2018, it’ll be 40 years since Charles died, and 30 years since his beloved wife and creative partner Ray (born Bernice Kaiser) passed away. And their groundbreaking work remains as influential as ever, with a new exhibition at the Vitra Museum exploring the careers of this dynamic couple.

Charles was born in 1907, in St Louis, Missouri. He studied architecture at Washington University but dropped out after two years to start his own architectural firm.

He married his college sweetheart and had a daughter, but it was meeting two brilliant Finnish architects, father and son Eliel and Eero Saarinen, which changed the trajectory of his life.

Eliel encouraged him to resume his studies at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan. It was here that he met Ray, who became his second wife in 1941. They moved to Los Angeles, and worked together from the start.

In Michigan, Charles and his good friend Eero had built a new type of chair from a new material called plywood. Now, in LA with Ray, he started to refine this process, but their plans were interrupted by World War Two.

With so many wounded soldiers, there was an urgent need for a new type of splint. Charles and Ray made one out of plywood. It was supremely practical, but its practicality gave it an accidental beauty.

That splint became a template for their work. “We don’t do ‘art’ – we solve problems,” explained Charles. “How do we get from where we are to where we want to be?”

Designs for life

After the war, a new generation of suburbanites wanted a new kind of décor, and Charles and Ray provided it. Their mission statement was bold and simple: “We want to make the best for the most for the least.”

Charles likened a good designer to a good host, anticipating the needs of his guests. The furniture they made was stylish and, above all, fit for purpose. No wonder it became the house style of America’s new moneyed middle class.

In 1947 they established their own studio, the Eames Office, in Venice, LA. For 40 years, it set the standard for every avenue of design. “We think of ourselves as tradesmen,” said Charles. “People come to us for things.”

“What works good is better than what looks good because what works good lasts,” said Ray. In fact, the two things went hand in hand. This was not a new concept. The Bauhaus had pioneered this functional approach before the war.

However Charles and Ray made it mainstream. Their designs were pleasing and accessible, attractive to young executives, not just artists and intellectuals. Charles introduced modernist design to middle America, but it was Ray who softened its hard edges, and gave it mass appeal.

Born in 1912, in Sacramento, California, Ray had trained as an artist, learning to paint in New York under the German Expressionist émigré Hans Hofmann. She didn’t feel that her eventual career strayed far from her initial studies, saying: “I never gave up painting, I just changed my palette.”

Charles understood that Ray was an equal partner in their creations, and he was always eager to acknowledge her integral role. “Anything I can do, Ray can do better,” he said. But the wider world was slow to recognise her talents.

This was the era of Mad Men, when even the most gifted women were often regarded as mere wives or secretaries. Ray was frequently forgotten, or dismissed as her husband’s little helpmate.

It wasn’t only chauvinism. Ray’s contribution was a lot subtler, less overtly visible to the untrained eye. She had a sharp eye for detail, he had a head full of big ideas. She sprinkled stardust on his designs, and gave his grand projets the human touch. She had a feel for colour, and a sense of fun. Without her playful input, his creations would have seemed austere.

Their complementary talents came together in the home they built together in Pacific Palisades, now known as The Eames House. Shaped like a shoebox, built of glass and steel, the exterior is all Charles.

Full of quirky objets d’art, the interior is all Ray. Who else would have thought to hang pictures from the ceiling, so you could lie on your back and gaze up at them?

Most modernist buildings are stripped of clutter, so as to show off the minimal architecture. Ray loved clutter. Her house was a cabinet of curiosities, a Wunderkammer full of curios that had caught her magpie’s eye.

Adventures in wonderland

Charles and Ray built their house in a meadow overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Its huge windows brought the great outdoors into their home. They planted eucalyptus trees around it, to soften its impact on the surrounding countryside.

This house was the perfect metaphor for their attitude to design. They didn’t try to impose their vision on the universe. They were curious about the world around them. Their work was a journey of discovery. Design was their way of sharing their discoveries with the world.

This childlike sense of wonder was reflected in the films they made, tackling everything from the Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire to the Dimensions of the Universe, from toy trains to spinning tops.

Many are only a few minutes long and a lot of them are now on YouTube. When they were made, these short films looked out of place in the cinema or on television. Online, they fit perfectly. This was the shape of things to come.

Charles anticipated the information overload of the internet age. “Beyond the age of information is the age of choices,” he said, prophetically, way back in the 1970s. His own films were wonderfully simple – masterpieces of clarity and economy, and often quite profound. “The same stars that shine down on Russia shine down on the United States,” he said, in a film he made about the US for Russian audiences, at the height of the Cold War.

Charles died in 1978. Ray died in 1988, 10 years later to the day. Half a lifetime later, their work remains the benchmark for all designers – not just for their aesthetic sense but for their irrepressible joie de vivre. Their mantras work just as well for any area of creativity: notice the ordinary; preserve the ephemeral; don’t delegate understanding; explain it to a child.

These back-to-basics mantras fed into everything they did, which is why their work always felt so fresh and different, not only user-friendly but also easy on the eye. Maybe the best example is their house of cards, a colourful, creative building game which I played with for hours on end when I was a child, with no idea that it was devised by the greatest design duo of modern times.

For Charles and Ray, design was a means to an end, rather than an end in itself. “One can describe design as a plan for arranging elements to accomplish a particular purpose,” said Charles.

“The extent to which you have a design style is the extent to which you have not solved the design problem.” Did they have a design style? Well, sort of. You certainly know it when you see it. But their best work was like a pane of glass. You looked through it, barely aware of it, too busy marvelling at the wonders of the world beyond.